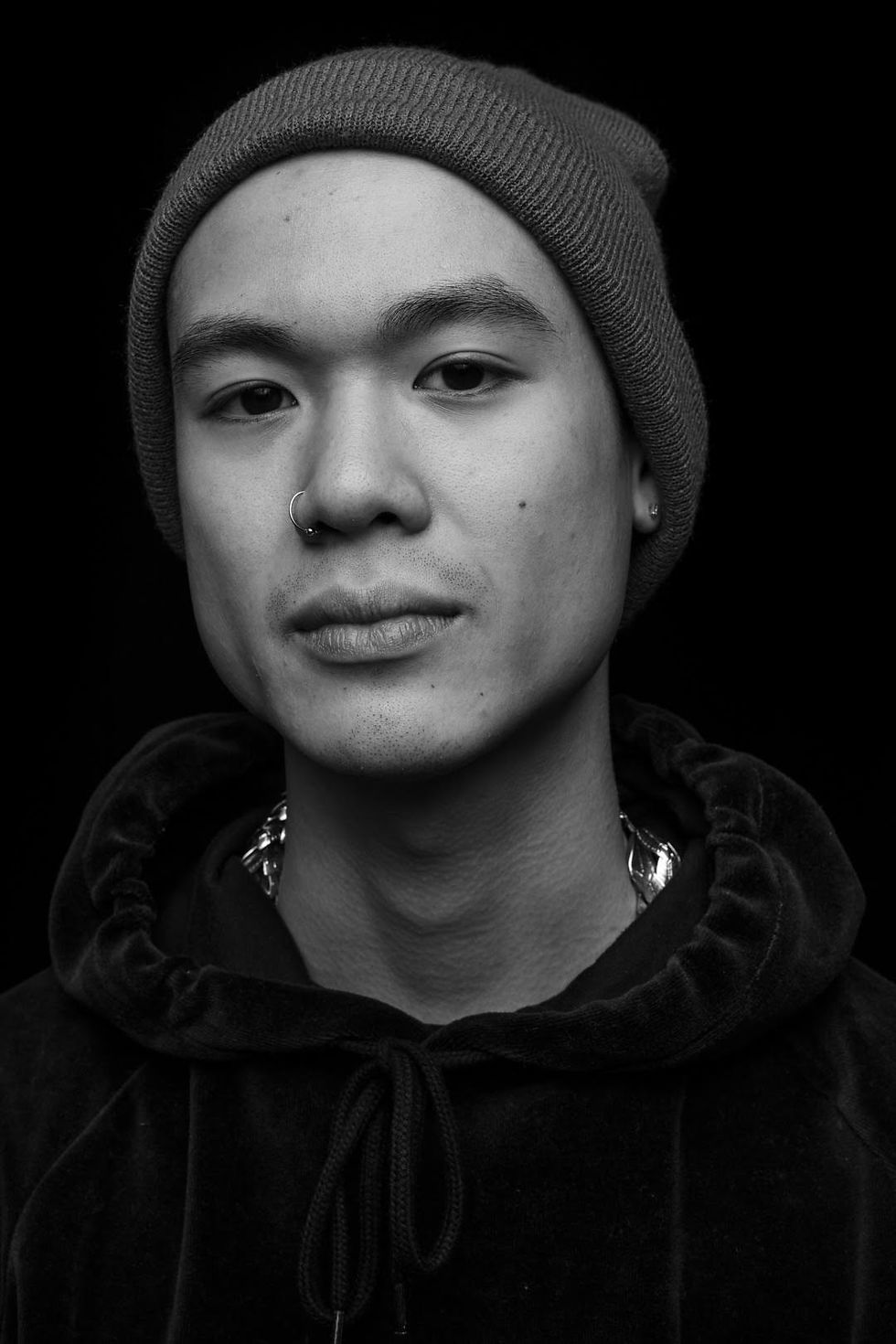

A Conversation With Poet Alex Dang

- Zachary Anderson

- May 6, 2021

- 12 min read

According to his “About Me” page on his website, poet Alex Dang has performed his work in 30 cities in seven countries. For four years straight he was the only Asian American to be part of the Portland Poetry Slam nationals’ team. His work has been featured in publications as wide and diverse as Huffington Post and the Harpoon Review.

In mid-March I interviewed the Portland-based poet. Our discussion was based around the piece below which led us to talk about the power of influence as well as our shared admiration for Kendrick Lamar.

For length and clarity, this transcript has been lightly edited.

LOYALTY. Music Video Greatest Love Story Ever Filmed

Rihanna spits gum into a dude’s car for the fun of it

and Kendrick finishes the fight for her because that’s

what love is. Then because said dude disrespected the

love, they steal his car to teach him a lesson and that

lesson is love’s gonna get you killed but pride’s gonna be the

death of you and you and me and you and you and you and me

and that’s the end of Romeo & Juliet except in this

version, the lovers don’t die. Everything that tries to

kill them, fails. Kendrick stands alone in the road,

surrounded by masked assailants. Eventually, they

rush towards the center where Kendrick, unbothered,

sees the naysayers sink into the street. Still boasting

about the loyalty he has forged, he watches those who are

unfaithful fall into the ground around him. Then, the

Bad Girl herself appears just to diamond duet the verses

into something so good that you can’t help but show it off

and that’s not ego when you have pride in your love.

There’s no shame in putting everything you have in love

and dying and in this song, that’s damn near impossible so,

why be humble? Why not hang off the ledge holding only

his hand? There are sharks swimming in the concrete and

their feet are dancing around them like ripples on a pond

and Rihanna has her hands on the wheel and so does

Kendrick and now they’re swerving in circles until a truck

crashes into them and they laugh because ride or die and

it ends with the two of them being pulled under slowly,

holding each other like they were slow dancing, like:

“If you go down, then I go down with you.”

What are the origins of this piece?

I would hope you would call the poem an ekphrastic poem which is the writer observing a piece of art and writing about it–– [John Keat’s] “Ode to a Grecian Urn” is a classic example. The idea is that you find something extraordinary and find beauty and magic.

I wrote this during quarantine when I was listening to a lot of music and I was also consuming the music on a visual level through music videos. I have always been a music video fan. Kendrick Lamar’s music videos have really brought them to another level. I remember when “Humble” dropped everybody was all about those extreme, wild visuals which carry on through in “Loyalty.” I think they were both directed by [David Meyers]. I love that connection of hip-hop being a platform in which you can imagine yourself being more or greater than what you are. You’re taking this piece of your identity and making it grander and expanding it.

Talk to me about why hip-hop has had such a heavy influence on younger Asian American artists. Using you as an example.

I remember talking to my brothers about this. We grew up with hip-hop and I think that was just because of where we lived–– our culture and who we surrounded ourselves with. I remember [my brother] Richard saying that at a certain point in the ‘90s people were usually just listening to grunge or hip-hop and my brothers gravitated more towards hip-hop because it was just around them more.

I think there was also a certain sense of my parents liking hip-hop more in that it reminded them of dance music, jazz, funk, and soul music that they listened to when they came to America [from Vietnam].

Really thinking about this, I’m looking around my room and I see Jordans’ and other pieces of hip-hop culture that signifies me really trying to put on that persona. And it was because I have always felt very emasculated as an Asian male and I think a lot of people see hip-hop as a very masculine, strong kind of art and that they also saw it as being dangerous during the late ‘90s and early 2000s.

So me being an emasculated, weak male, I wanted to align myself with something like that to make myself bigger than I already was.

Would you actually describe yourself as that or was that your environment telling you that’s what you were?

A little bit of both because–– I think it was mostly about reaching a level of masculinity and wanting to prove myself.

A lot of my viewing comes from me being a cis male. I know I can speak on that for sure. And a lot of the other people I was interacting with were male, and in that context of masculinity I feel I was speaking a lot to that.

You already said that quarantine has given you this opportunity to really do deep dives into the artistry of music videos. What drew you to focus in on "Loyalty" and write this piece?

I think specifically what I got from “Loyalty” were people saying Kendrick and Rihanna looked really cute in it–– and they did–– but I also know that they aren’t in a romantic relationship. But for all intents and purposes they are kind of in a relationship in the video.

But as I was analyzing frame by frame this love that they have between each other, it’s not romantic but it’s also not platonic either. It is this very specific kind of love––it is a deep, affectionate kind of care. There’s a moment where Kendrick jumps to Rihanna’s defense simply because that’s what love is–– just a knee jerk reaction.

I saw so much of these acts-of-love that were neither romantic, platonic, nor familial. They were just acts-of-love. There’s this one moment where they’re surrounded by sharks: they’re not panicking, they’re just moving through the sharks together. And then they’re driving together. I appreciated that portrayal of that kind of love.

I’m not the best love poet because I always try to write something that either shoots for the moon and reaches everybody or focuses in on something very hyper specific and talks about myself and not speak for anybody else.

With this music video I wanted to write a love poem, but I couldn’t think of a particular love in my life. I just wanted to comment on this love that I think we all have in our life–– or at least we have these kind of friends or people in our lives that we don’t realize that we love.

This piece is very conversational and you’re succeeding at telling us about this kind of love and despite you saying you’re not the best love poet, it’s engaging in that specific way that you were aiming for.

I wanted the imagery to speak for itself. I wanted the descriptions of the video to be accurate but also make clear that I am relaying what I’m seeing and what I’m getting out of my viewing this video.

I like the idea of being able to see love in everything and anything. So being able to pull this from the radio single and Kendrick’s last album and the radio bop and the fact that it samples Bruno Mars’ “24 Carrot Gold” and the fact that Rihanna’s in it and that it’s very catchy. It’s not Kendrick’s most complex song–– it doesn’t have to be–– because it’s not trying to be complex. It’s not trying to be “HUMBLE.” or “DAMN.” It’s not trying to be “good kid m.A.A.d. city.”

I love the simplicity and complexity in it. It’s just trying to show loyalty. It’s trying to show this love and relationship and this idea that it is what it is.

When I read the poem, I also watched the video and some of his other videos. “Loyalty” has all the elements of his best songs without being one of them.

I agree. It’s definitely not over-the-head, but it definitely encapsulates the idea of a music video. It tells a story, but it doesn’t do the thing where it’s both a short film and a music video. It doesn’t do the thing where it’s an extended music video with scenes in the middle of the song. It serves its purpose so well–– it’s a sweet and heavy meal that you order, it’s consistently going to be the same thing.

It’s not like “Alright” where the video was longer than the song.

“Alright” is a wonderful music video, but it’s not one you can consume every day.

“This is America” [by Childish Gambino] is one of the best music videos out there, but I cannot watch it every day. Even some of the other Kendrick videos like “DNA.” are like that. I love Don Cheadle but I can’t watch it every day because it’s so intense.

In “Loyalty,” you see Rihanna laughing. You see her joking around with Kendrick. It’s a very whole-hearted music video; and that’s what I wanted to capture in the poem–– how sweet this song is–– in a way that I didn’t initially realize how sweet this song is. And I wanted to explore that theme in the poem.

Looking at the history of music videos, this is one that can only be made in the digital age. Like before the internet became widely accessible, most music videos were just the artist or band standing in front of a fish-eye lens and performing.

That just reminded me of Seal’s “Kissed by a Rose” which is just him in front of big floodlight and scenes of a Batman movie.

[laughter]

Also, “Loyalty” and all of Kendrick’s music videos in general, they’re not trying to be viral sensations–– Taylor Swift’s “Calm Down” and “Bad Blood” were blatantly meant to go viral, for example.

I love the idea of thinking of rules and restrictions in a medium instead of treating a medium as a sandbox to play in. And in the music video sandbox, you get to play with visuals, camera angles, costumes, dancers, and all these sorts of different things.

When we’re thinking about poetry–– page versus stage–– I can make a reader visually read something in a way that will slow it down or make it go faster. I can emphasize certain phrases and break the line in certain ways that I can’t do when performing. On the flip side of that, I can perform it in a way that the page could never capture.

That’s why I’m always curious and interested in the experience of consuming music as is versus as a music video–– even how you’re listening to music with either headphones, speakers, or while driving.

In your other “What Kind of Asian Are You” –– which was the first piece of yours that I was introduced to–– you incorporate not just references to music but also a lot of visual motifs.

Before I was a poet and writer, I wanted to be a rapper and actor. My writing style is informed by that specific performance style of being on stage and learning improv.

One of my favorite things about hip-hop and its rhyme schemes was the idea of a constructed metaphor–– this entire thing of picking one topic and rhyming everything related to it, making it all related to a single overall theme.

Like, I use water a lot as a metaphor for myself–– for one–– being bipolar and moving through fluid stages all the time. Also, the idea of sadness and depression being represented by rain which can also mean something good.

In the hip-hop world, when you talk about water, you’re also talking about flow and if you’re talking about flow, you can be talking about how smooth you are. Then from smoothness you can talk about silk and from there we can go back to me making jokes about being Asian and boom! We’ve reached the punchline before you have.

That’s how I was playing around with “What Kind of Asian Are You.” It was me thinking about how I’ve heard every Asian joke before and how I’ve made better Asian jokes than the ones I’ve heard so I’m just going to break all of this down to show how dumb it is.

Watching you perform that piece I was reminded of Malaka Gharib’s graphic novel “I Am Their American Dream.” It’s all about identity and how it’s not only being defined by herself but by others as well.

I hope that the main point of my poetry and when I teach workshops is to understand where you are as a person.

I always think about the poem by Eve Ewing that says, “I wanted a map not to know where things are, but where I am.”

I love this idea so much because it feels like my life. I know that I am the youngest of my family. I know I am “Dang’s boy.” I know I am Richard’s youngest brother. I know I am a [University of Oregon] graduate. There are all these landmarks around me that inform who I am, but they still haven’t told me exactly where I am. But I’m still able to figure out from all of the things around me where I actually am.

There are folks who know exactly where they are and don’t need a map, but they should probably learn where things are in the world.

I remember during a workshop I had with you, the poets you were referring and referencing to were Black poets who were writing about Black issues–– which are just American issues, by the way. What aspect of their artistry speaks to you and how does it inform you?

For me, it was growing up in Portland and not seeing a lot of folk of color. So, a lot of the narratives that I tend to lean towards are emotionally charged topics that resonated with anxiety and depression and misunderstanding.

In the beginning my poetry was emotional and free in form. It was that raw emotion that I was initially relating to. But then there’s a point where you have to start sharpening that emotion into something, and that led me to consuming more poetry and seeing that a lot of people talk about sadness in the same way which made me want to talk about sadness in a new way.

“What Kind of Asian Are You” is so open ended because it was just me trying to answer that question. But when I went a little bit deeper into it, I didn’t know how to interact with that subject. I didn’t want to talk about race because I didn't know how to approach it.

Also, the white poets that I competed against and the ways they dealt with sadness were not the same ways you would deal with race. I started thinking that I couldn’t apply the same tools to dealing with my anxiety and my sadness with the same way that I deal with my race.

That’s why I felt so misunderstood for so long, because I kept thinking, “Oh! It’s not because I’m Asian, it’s because I’m sad.”

But I realized that they are two different things and only fixing one of them doesn’t make the other go away. In realizing that, I started trying to figure out how to talk about race issues.

It went from just speaking about race issues from a black-and-white angle to being tired of giving educational lessons of why I’m tired of being Asian.

Seeing other poets of color talk about this same racial fatigue and talk about these microaggressions and talk about themselves in a way where it wasn’t highlighting their race issues, but just highlighting their life, and coming to the point of talking about why this is important.

I was missing the objective. I knew who I was, and I was exploring my relationship with the world. But I didn’t know what the point of this was.

I started trying to figure out what is my poetry trying to point out? What’s its objective? From there, it has evolved over the years and right now it’s just trying to understand where I’m at. So now I’m getting more and more information on how to build up and update my map.

I’ve been officially diagnosed with bipolar disorder, which means I can now actually get my mental health treated. I’m talking to my family about these things and breaking generational communication barriers that we’ve had forever. Quarantine has made me closer with my family. So I’ve realized more fully my relationship as a queer Asian American as well as my relation to colorism and where I fit in my relation to Southeastern versus Eastern Asian politics.

This is all helping me realize that it is so, so important to know where you are. I want to emphasize this to anyone who hears or reads my work. Know where you are and tell your story the best way you can.

To comment, I think what artists and creators who are further along in their journeys realize about influence is that it’s a direction but not a destination.

Yes, and I love being able to identify my influences and I like that being person who is able to put people onto other people like, “You like that? Check this out.”

I love that lineage and I think that’s why I love hip-hop because it’s okay to name drop and to say who your idols are. In the actual DNA of hip-hop and the instrumentals, you sample from music from the past and make it something new.

I know there’s a song by A Tribe Called Quest–– “Electric Relaxation” –– that is sampled by J Cole in his 2013 album. They touch on the same subject but they’re different songs with the same sample. It’s cool because I knew about J Cole before I knew about A Tribe Called Quest. I got to put that relation together later.

I don’t think anyone should be faulted for how they got into something. Lots of people are purists about stuff and I used to be the same way. I thought that was the only way to verify myself and show I belong by over-proving with knowledge.

What is a general piece of advice you have for young artists and creators who are just beginning to explore their chosen craft?

It’s a process. If you’re not writing, you should be reading. If you’re not reading, you should be editing. If you’re not editing, you should be writing, and so on.

Also, it’s okay to model yourself after someone you see a little of yourself in. Try emulating their voice to figure out why you like them and why it fits your voice.

Cite your artists, of course. There are plenty of poets out there who get inspired by other poets and still make their own mark.

There is a lot of strength and power from emulation.

If you like stories like this, subscribe to Chopsticks Alley.

Zachary FR Anderson

Chopsticks Alley Pinoy Contributor

Zachary FR Anderson is SoCal born and NorCal raised. He is an Occidentalist, writer, and lover of books. He resides in Sacramento.

Detailed and practical, this guide explains concrete rebar in a way that feels approachable without oversimplifying. The step by step clarity is especially useful for readers new to the subject. I recently came across a construction related explanation on https://hurenberlin.com that offered a similar level of clarity, and this article fits right in with that quality. Great شيخ روحاني resource. explanation feels practical for everyday rauhane users. I checked recommended tools on https://www.eljnoub.com

s3udy

q8yat

elso9

Using technology to increase access to youth mental health support may offer a practical way for young people to reach guidance, safe-spaces, and early help without feeling overwhelmed by traditional systems. Digital platforms, helplines, and apps could give them a chance to seek support privately, connect with trained listeners-orexplore resources that might ease their emotional load. This gentle shift toward tech-based support may encourage youth to open-up at their own pace, especially when in-person help feels too heavy to approach.

There is always a chance that these tools-quietly make support feel closer than before, creating moments where help appears just a tap away. Even a small digital interaction might bring a sense of comfort. And somewhere in that space, you…

شيخ روحاني

رقم شيخ روحاني

شيخ روحاني لجلب الحبيب

الشيخ الروحاني

الشيخ الروحاني

شيخ روحاني سعودي

رقم شيخ روحاني

شيخ روحاني مضمون

Berlinintim

Berlin Intim

جلب الحبيب

سكس العرب

https://www.eljnoub.com/

https://hurenberlin.com/

جلب الحبيب بالشمعة

Wedding Venues In GT Karnal Road. Wedding Venues GT Karnal Road Book Farmhouses, Banquet Halls, Hotels for Party places at GT Karnal Road Ever thought of enjoying a multi-theme Wedding Function while being at just one destination? If not then you must not have visited Farmhouses.